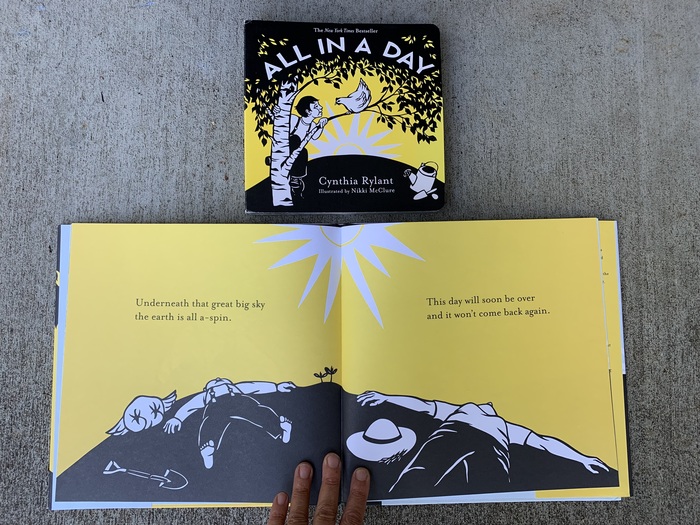

BRAVA Award Winner 2025 – Nikki McClure

Nikki McClure

2025 Special Choice Category:

Children’s Book Illustrator Award (Puget Sound region)

This award supports the work of contemporary visual artists from the Puget Sound region who work in the field of Children’s Book Illustration. Work may include original illustration included and published within the book format, and designed for a readership of 16 years or under. Work can include book cover, inside illustrations, and whole book design, including but not limited to graphic novels, e-books, interactive books, picture books, chapter books, works of fiction and non-fiction, zines, reference books, artist books, and pop-up books.

Nikki McClure is a children’s book illustrator and author based in Olympia, Washington, best known for her intricate paper cuts and evocative portrayals of life in the Pacific Northwest. Raised in Kirkland, McClure developed a deep connection to the Salish Sea through ferry rides, forest walks, and explorations of the shoreline. Her early curiosity about the natural world led her to study marine biology and natural history at The Evergreen State College, where she began combining art and science as a way to understand and celebrate home.

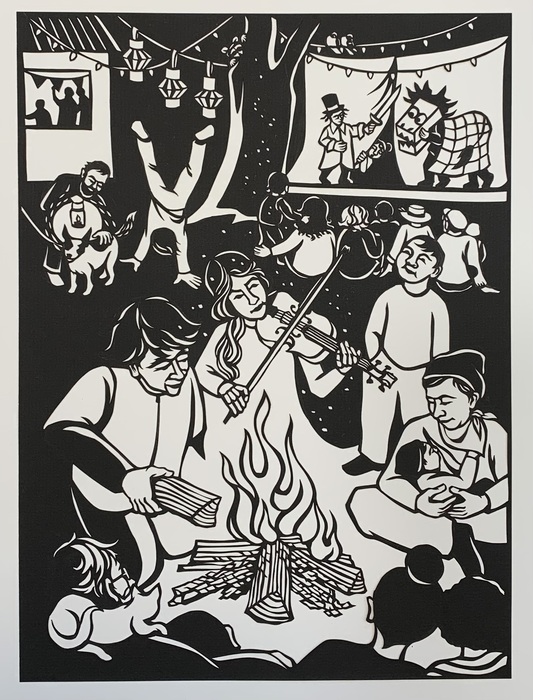

In 1996, while creating her first children’s book, Apple, she began cutting paper with an X-Acto knife, developing her signature style: bold, hand-cut images that reflect a sense of place, community, and seasonal rhythms.

Since then, McClure has authored and illustrated sixteen children’s books and illustrated eight others, receiving national recognition, including New York Times honors and a Washington State Book Award. Her work has been exhibited in museums and bookstores across the U.S. Through her books and artwork, McClure crafts a vivid and tender connection between young readers and the natural world of their home.

Artist Statement

I take the long way to work each day. I step out of my front door and hear the birds talking. Today, it was an eagle laughing. I walk down to the beach and see if anything interesting washed up in the night, then I head up a trail into a cedar forest. I hop over a creek and puddles and finally make it to the road. I head down the street to my home, open the front door, walk down the stairs to my studio, and begin.

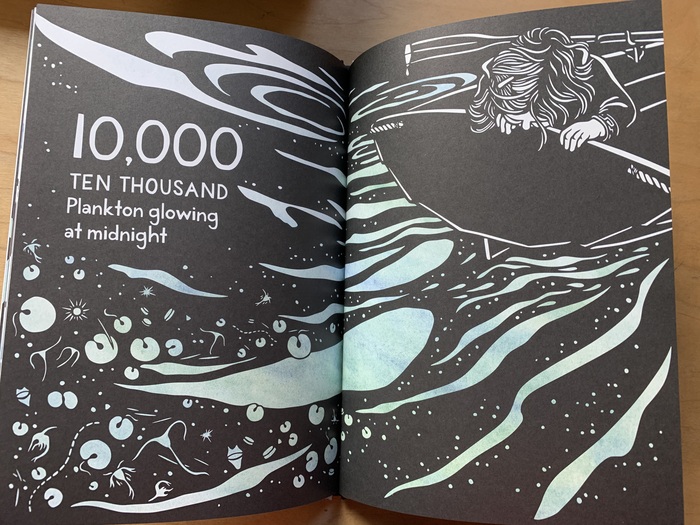

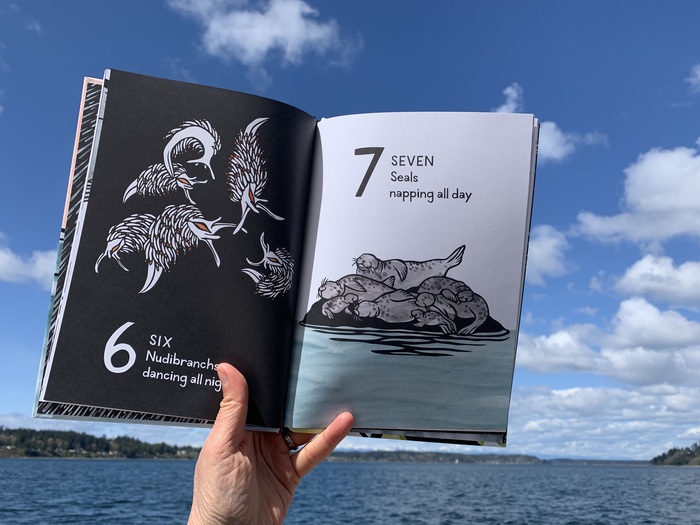

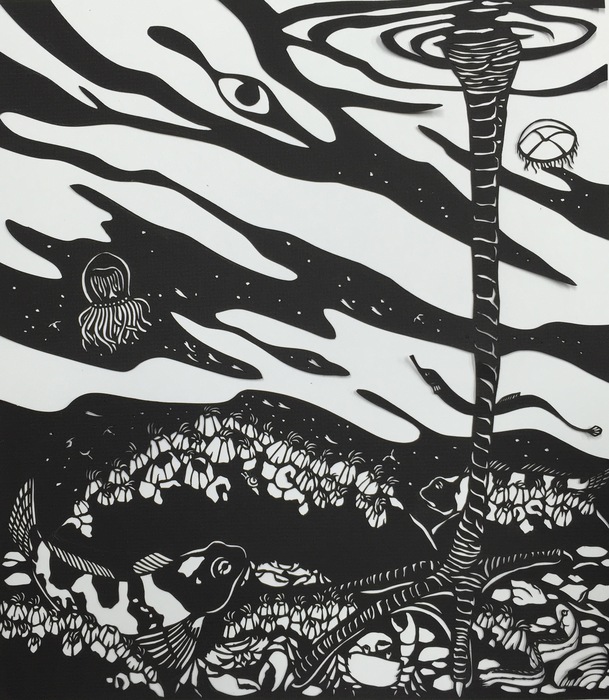

I get a black piece of paper and start cutting out a story. It is meditative work with simple tools: a pencil and an X-Acto knife. I crack open a window and listen to robins and siskins. Accompanied by their songs, I start cutting out the part of the image that scares me the most, the part that I am most worried about messing up. If a mistake is made, I continue on, for now, I am free to experiment. There is chance in mistakes. I choose to cut paper for these chances. There is no erasing, painting over, or deleting; there is only making do and experimenting with making better. Cutting paper creates bold lines that don’t allow for much detail. I am a scientist who trained my eyes to see minute distinctions. As a student, I would spend days trying to draw a fly perfectly, yet the fly had a torn wing. Using a knife to “draw” frees me from attempting perfection in an imperfect world. I aim to distill the essence of a bird, cutting just enough to know that here is a song sparrow. I cut during the morning when the light is best, and a bit in the afternoon, lit by my curiosity to see the image develop. By the end of a week, an image appears. The paper that remains is fragile, yet strong and connected like the world that I depict. The final papercut shows evidence of my hands working. Pencil lines faintly shimmer, and the paper creates subtle shadows. Neither a print nor a drawing, the paper becomes a delicate sculpture boldly holding a story. I then get my broom and sweep up the tiny scraps piled on the floor. I head outside for another walk and for a new idea of a story to appear.

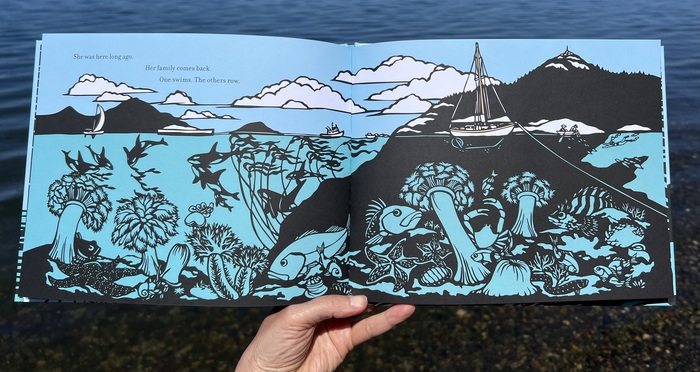

The past few years have been full of change for me. In response to limits on movement and materials, I hunkered down in place and used stacks of washi paper collected from art trips to Japan. Creative assignments from Orion Magazine to illustrate stories by Barry Lopez and Rachel Carson allowed me a chance to experiment with new approaches to papercutting. Instead of cutting uniformly black paper, I painted the washi with sumi inks and then cut from the painted papers. Washi paper is soft and cuts like butter, yet it is tenaciously strong and reluctant to be removed, holding on to the last fiber. The surface is unforgiving to a pencil, so I cannot sketch out a plan. Adding to the challenge, recreating a particular painted pattern is impossible. I have to cut and trust. It is exhilarating to make at the edge of complete disaster at any moment. I cut in response to the changing hues of the ink and feel as if I am in conversation with the paper. I don’t know what the finished image will look like until it is completed. It is exciting, this not knowing. I have been cutting paper since 1996 and am still enraptured in the process of a picture emerging from the darkness as if it were there all along, waiting for me.

I approach writing books the same way. I find ideas on my morning walk or low-tide beachcomb. Words come from snippets of speech overheard or from questions of my child when he was small. Editing text for children’s books is a lot like cutting paper. Tiny bits are removed, and a story takes shape. My stories are based on a lived experience of place. I find reality to be fantastical and generative of wonder-filled questions.

My work embraces the nonhuman world as part of my community: birds, fog, and bumblebees. I draw from memories of thousands of generations’ connections to water and wet soil: picking berries, watching gulls drop clams, and keeping community with stories near a fire. I focus my work on connecting young people and their families to this deep connection of place and time, to their home by the water.

I make books for children who ride ferries to islands; who beachcomb, hopping from log to log, finding branches and boards to build forts; for children who wonder who lives in the cold green water and then hop in to swim with jellyfish at high tide. I make books for children who wait for the first ripe salmonberry and then in September, have fingers stained purple from salal. I make books for those who know days of rain and who sit happily in mud puddles. My art aspires to make books of home for the children of here. It is an honor to write and illustrate children’s books, crafting an awareness and wonder of place. The message I aim to instill at an early age is as deep as the sea: this is your home. See your home. Know your home. Love your home and take care of it, you lucky kid of the Salish Sea.

I keep wondering, digging deeper into knowing my home, making books for children everywhere, but especially here.